Episode 16: The Thirteen Postures

[memberonly}

Sorry for taking so long. This lesson / video involved about a month’s work, several re-writes, re-shoots, and two days of editing the final video, all while trying to keep afloat and working around a now complicated work schedule. Thank you for your patience and understanding.

Video Chapter markers:

Those little blue dots in the timeline are chapter markers. A transcript is posted further down this page.

- 00:21 Why is it so confusing?

- 06:24 Common explanations

- 07:59 Mechanics of combat

- 09:23 Flavours of Mass and Velocity

- 10:01 Inertia, momentum, and kinetic energy

- 12:50 Conservation of momentum could be more dangerous

- 15:00 Squishiness vs Boingy-ness

(Elastic modulus) - 17:35 Tensile, good. Shear, bad.

- 19:00 Peng is a natural instinct.

- 19:40 Softer is harder.

- 20:35 Hard power vs Soft power

- 22:15 Pressure: Ji and An

- 26:20 The 4 Directions (Peng, Lu, Ji, An)

- 27:46 Angular momentum (the 4 corners)

- 30:10 Splitting

- 31:03 Plucking

- 32:15 Breaking the needle

- 34:10 Sharpening the broken needle

- 35:55 The 8 trigrams in the hands

- 36:50 The arms are not legs

- 39:50 5 elements in the feet

- 40:37 Force

- 41:23 Space

- 43:59 Centre

- 44:06 Look right

- 45:14 Gaze left

- 47:57 All together now

- 48:55 13 posture in the tai chi routines

- 51:00 13 postures in self defence

- 53:00 The challenge of using real words and physics

Any real martial skill in tai chi depends on an understanding of the 13 postures. But there is so much confusion about what the term “13 postures” even means, that most teachers are better off not talking about them. In fact, most don’t deal with them in depth. This may be either because the teachers don’t think they are important, or because they don’t think the students will understand.

But I do like to teach them, in unending depth, because I am a foolish 鬼佬 tai chi nerd. But I do my best to teach them using modern language that actually makes sense.

The definitions I use for the 13 postures are not based on the movements or martial techniques of the same name. They are definitions of the mechanical efficiencies that those movements are designed to teach.

Linear Momentum and Pressure

p = mv,

Momentum = mass • velocity

P=F/A

Pressure = Force / Area

- BOING:

pěng 掤:

Maintaining a centripetal geodesic of maximum tensile modulus. This makes attacking on your centre the path of greatest resistance. The skill itself is the result of cultivating a natural instinct and learning to subsume contradictory instincts. - ROLL:

Lǚ (no font for this character, substitute:捋 ):

the low shear modulus created by the elimination of reactive tension in the class three levers of the arms, and by balancing the body in a way that reduces lateral tension. This makes deflection by the centripetal geodesic automatic and effortless. - CRAM:

擠 (s挤) (jǐ):

the increase of forward pressure by reducing the surface area at the point in spacetime where force engages with the opponent. - PRESS:

按 (àn) :

the decrease of the opponent’s pressure by increasing both the surface area and the time in which the opponent’s force is required to engage.

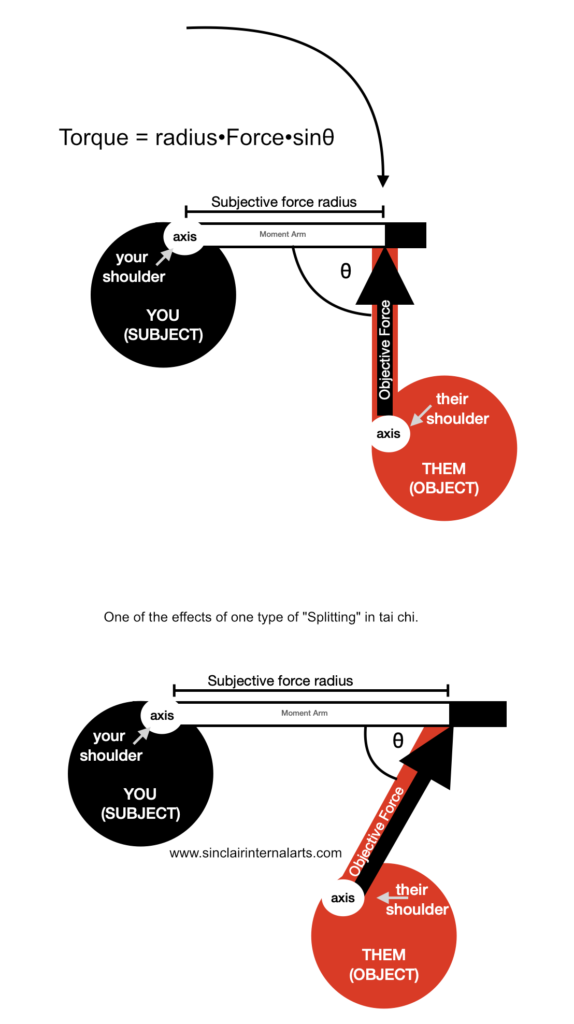

Angular Momentum and Torque

L = mvr sin θ

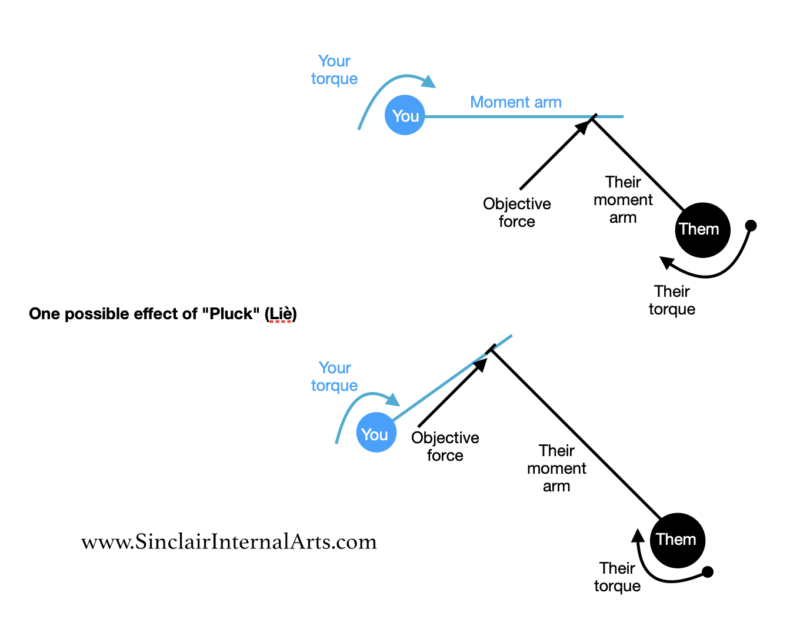

- PLUCK:

採 cǎi :

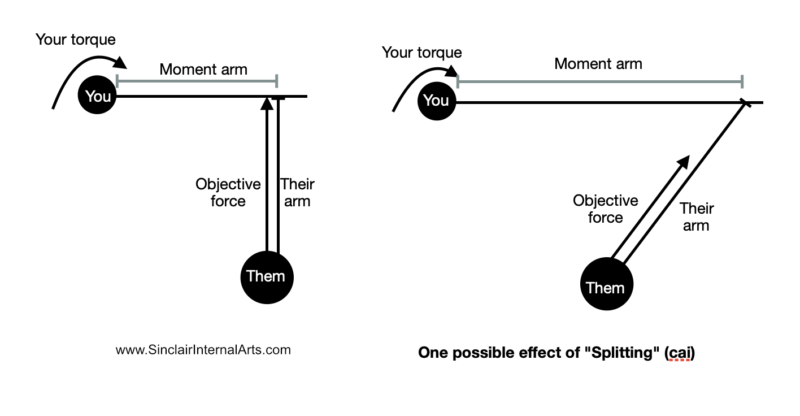

increasing the objective force radius (the distance between your opponent’s centre of rotation and the point where they apply force to you.) and decreasing their force angle. - SPLIT:

挒 (liè):

increasing the subjective force radius (the distance between your centre of rotation and point where you engage your opponent’s force/resistance.) and reducing the angle of their attack. - TRAP / INTERCEPT / SHEAR:

肘 (zhǒu):

causing shear stress to the opponent, bypassing or disrupting the opponent’s tensile modulus - ABUTTING:

靠 (kào) :

Shortening your own radius in order to counter efforts by the opponent to bypass your tensile geodesic.

Force, Space, and Leverage

- Apply Force: 進步 (Jìnbù) “progress, improve, advance”

Using the legs to apply force to a target. - Create Space: 退步 (tuìbù) “retreat”, “take a step back”

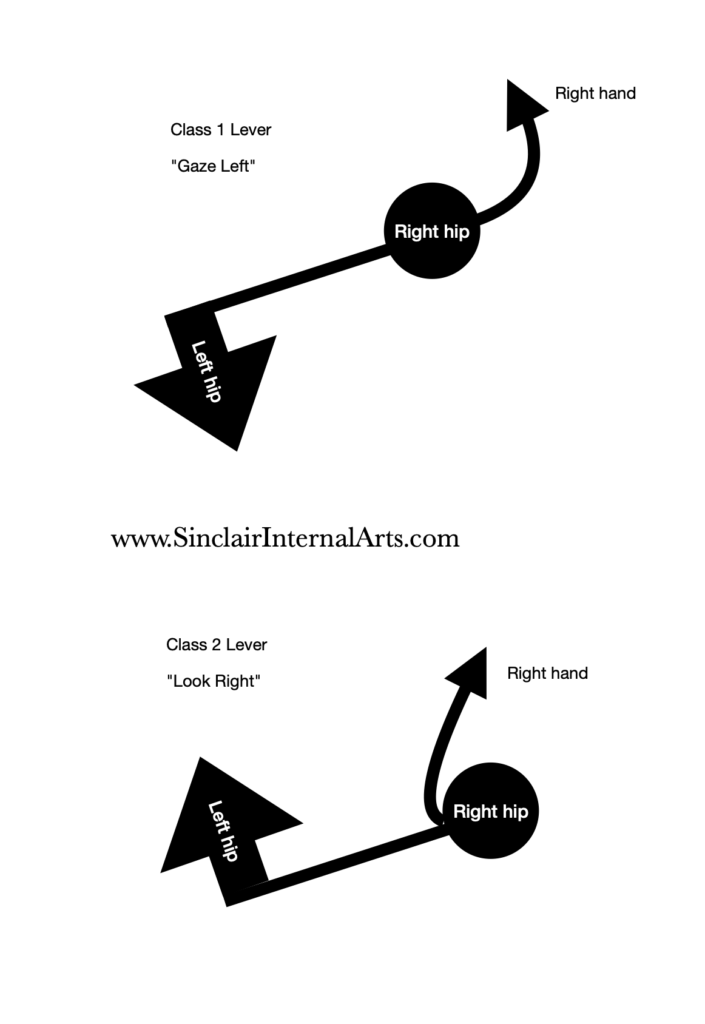

Using the legs to create space between you and your opponent. - Class 1 Lever: 左顧 (zuǒ gù) “gaze left”

Pivoting the body away from the target to attack with the arm that is on the other side of the fulcrum - Class 2 Lever: 右盼 (yòu pàn)

Pivoting the body toward the target to attack with the arm or body on the same side of the fulcrum. - Choose an axis of rotation. 中定 (zhōng dìng)

To select or define the central axis of rotation in a given moment.

Transcript:

This is not a totally accurate transcript. There was some editing and improvisation involved.

In this video I will attempt to clean up one of the messiest teachings in martial arts. Traditional martial arts have lots of classic teachings that make little to no sense in modern scientific terms. It is not that they involve some sort of magic that science can’t explain. It is just that some things were taught non-verbally, and/or documented by people who were not scientists, and who were not concerned with using vocabulary that everyone could understand. If their students understood what they were talking about, that was all that mattered.

Now we have this legacy of meaningless terminology that gets interpreted in weird, inconsistent, and mystical language that has no place in realistic training. Some people may be resistant to scientific analysis of their art, perhaps thinking that it will lose some of its profound or subtle meaning. But I find the opposite is true. A realistic study of the science and psychology of the art is necessary to appreciate just how amazing it is. But we need to start with practical language if we are going to achieve practical skill. The challenge is breaking down something as profound a thing as a traditional martial art, in terms that beginners can understand, in a way that will encourage students to train more, and give them the hope that comes with a basic understanding.

It has been said that the secret to tai chi, the master key to martial art skill, and a defining characteristic of the art, is found in what is called the 13 postures. But it can be very difficult to find a satisfactory explanation of what the 13 postures are or how they relate to combat. They are certainly not what they appear to be, on the surface.

Now, if you research the 13 postures, you will find lots of information. In fact, you will find too much information. The search will take you into a rabbit warren of complexity, metaphor, simile, mysticism, hyperbole, multi-dimensional interpretations, some terrible translations and a fair bit of fertilizer. There are classical treatises that seem like the scribbled notes of a stoned undergraduate student of Milesian Philosophy. There is a treatise called the “Song of the thirteen postures” which assumes the reader already knows what the 13 postures are, but doesn’t explain anything about them. It is like having a driver’s manual called “Song of the internal combustion engine.”

But I digress.

The thirteen postures are not postures or martial techniques, or movements. This is just another example of something that has been poorly translated from Chinese, even when you are translating into Chinese. The language has always been ambiguous, because the traditional way of learning was experiential. There was no need to explain the physics of it because, for one thing, few people studied physics, and for another, most instruction was non-verbal. There is a long tradition of martial arts being taught without explanation. “Don’t think. Just move.”

The thirteen postures are actually, at their core, 13 mechanical principles that create tactical advantages in a fight.

I really think that the pedagogy can benefit from having, from the very beginning, some understanding of the science involved. But to do that, we need some sort of common vocabulary. And the traditional Chinese terminology is not very helpful most of the time.

We also need some sort of approach to first principles. That is, we need a context to start with, even if first principles get redefined later on, as happens with science, and certainly happens with martial arts.

Martial arts like tai chi often base their philosophy on the concept of yin and yang. That is a bit like saying that classical physics is based on matter and energy, or stuff and the space between the stuff. We need clear and unambiguous vocabulary if we want to communicate basic concepts to the masses, so I like to start with mass and velocity. Sometimes I think that traditional martial artists are too fond of puns.

But I digress.

How can we explain the 13 postures to beginners?

What explanations do exist, tend to use obscure Chinese words and concepts that even Chinese people don’t understand. They talk of the five elements (metal, water, wood, fire, and earth) being in the legs, and the eight trigrams (heaven, earth, fire, water, thunder, mountain, lake and wind) being in the hands. Then they take you on a journey through ancient philosophy, poetry, cosmology, medicine and interior decorating, that have nothing to do directly with martial arts. And then the writers don’t even have the courtesy to stop and say, “But I digress.”

Most Chinese people don’t understand ancient Chinese, and those who can read ancient Chinese don’t understand tai chi. Reading what is translated in Chinese about tai chi is like reading the writings of Chaucer translated by Gregory Corso. You are left trying to guess whether “penguin dust“ is: a) something you buy at a pet store. b) fallout from an exploding penguin. c) or a something you see happen after you see a penguin vacuum, or a penguin wash the dishes.

But I digress.

When you ask, “What are the thirteen postures?” you might get a list: Advance, retreat, look right, gaze left, central equilibrium, ward off, roll back, squeeze, press, pluck, rend, elbow, and shoulder.

But the meaning of those words will change depending on the context in which they are used.

The teacher might be referring to a structural property, or a mechanical characteristic, or a kind of martial technique, or a method of applying that technique. They might be referring to tactics, or strategy, or attitudes. They might be referring to attributes or habits developed through training, or to mental or emotional states. They might be referring to the effect that the 13 postures have on you, or to their effect on the opponent.

What you seldom hear, if ever, is an explanation of the physics involved, or a clear deconstruction to the elements that make up the whole. That is what I want to try to do today.

Today, I want to to talk about the thirteen postures in terms of the mechanisms of self defence. I will what each of the 13 postures is, and perhaps, how they combine to form the gestalt that is martial skill.

When you watch what people typically call a demonstration of the 13 postures, they will demonstrate some choreography, either a solo movements or a partner exercise. But these movements are not the thirteen postures, they are movements we used to teach the thirteen postures. They are not, themselves, supposed to be martial techniques. They are supposed to be ways of practising the 13 mechanical efficiencies that make martial techniques work. In a fight, you apply all 13 of them together. Really? Even the five elements in the feet? All at once? Yep. Eventually.

Okay. Let’s start.

Martial art techniques are all about mass, velocity, and the ways that those two things change. But the combination of mass and velocity of an object can be used to describe different characteristics.

Classical physics has several ways of describing and measuring different ways that moving mass can interact with another mass.

There are some universal characteristics of mass which matter to martial arts.

INERTIA:

The first is inertia. Inertia is the stubbornness of mass. Whatever an object is doing, it will keep doing it the same way unless something else forces it to change. If it is moving at a particular speed, it will keep doing that until something else forces it to change speed.

MOMENTUM:

The power of that stubbornness is called momentum. If you multiply the mass of an opponent by the speed they are running toward you, you can get an idea of how much you are going to move when they hit you. The less you weigh, the faster you are going to fly.

KINETIC ENERGY:

Another power of that stubbornness is called kinetic energy. Kinetic energy will tell you how much it is going to hurt you when they hit you. For this calculation, mass is half as important as it is with momentum. But the velocity is exponentially more important.

How much more important? Well, consider this example.

A one-tonne truck going 1 km/h has approximately the same momentum as a golf ball going 43,573 km/h. (35 times the speed of sound.)

But the kinetic energy of the truck is 77 Joules, while the kinetic energy of the golf ball is 3,362,115 J.

Which one would you rather be in front of?

(side note: many tai chi fighters run into trouble because they spend all their time working with momentum and forget all about kinetic energy.)

Now, if you have every watched billiards, you’ve seen a cue ball hit an another ball so perfectly that all the momentum of the cue ball gets transferred to the second ball. The cue ball stops dead, and the other ball moves at the same speed that the cue ball had been going. But if the cue ball were twice as heavy as the second ball, a similarly efficient transfer of momentum would make the second ball go about twice as fast. This happens because p=mv, and since the second ball can’t get heavier, it has to go faster.

This sort of thing happens when you punch someone in the head. If you can transfer the momentum of your whole body, through your fist, into the opponent’s head…just the head… then said head will move much faster than your fist. This explains some of the unbelievable demonstrations that you see in tai chi classes. (I say some, but not all.)

So, imagine if you could transfer all of the momentum of the one-tonne truck going 1 km/h into a golf ball, the world would be a much more dangerous place than it is. A nudge by a truck would make a golf ball go 35 x the speed of sound.

It is fortunate that perfectly elastic collisions are rare in nature, and that heavy objects are too stubborn to give all of their momentum to just any tiny object they hit. Otherwise, rain drops and other things bouncing off your windshield would change the destiny of the planet even more than they already do, and the last thing to go through a bugs mind would not be its butt.

ELASITC MODULUS

So, this brings us to squishability. When someone pushes you, do you get squished, or do you hold your shape?

There are three main kinds of squishiness. Linear squishiness, lateral squishiness, and all-over squishiness. Or squashable, twistable, and packable.

Straight squishiness is determined by a thing called the Young’s modulus, or tensile modulus. If someone tries to squash you and you don’t change shape much, and you go right back to your original shape when they stop squashing, then you have a very high tensile modulus. Diamond has the highest tensile modulus. It is very difficult to squash a diamond, because it is pre-squashed.

If someone tries to bend you or break you, and you can’t be bent or broken, and you bounce back to your original shape when they stop trying, then you have what is called a high shear modulus. You might think that this is a good thing. But it can make you very easy to throw around. Your limbs become like handles and your tension becomes a lever that your opponent can use against you.

You might be able to pick up a brick with two fingers. But try picking up a water balloon with two fingers, or grabbing a fresh tomato seed with chopsticks.

If someone tries to pack you into a little ball and wrap you up in a hairnet, and they succeed, then, wow, you have a very low bulk modulus.

One of the most important tools in tai chi is the ability to cultivate a very strong tensile modulus, along what I call the centripetal geodesic. The centripetal geodesic is the curved path that you create through your body so that force follows the path of highest tensile modulus. Usually we talk about the path going through you into the ground. It is the least squashable path to the ground. But it can go to your own centre, or any centre that is strategically suitable. The centripetal geodesic is the thing you push with, strike with, twist with, and balance on. It is also the thing that you meet your opponent’s force with, when they target you successfully.

With practice, you can develop the ability to spontaneously redirect an opponent’s force into the ground without doing anything, or without applying any extra force. This is actually a natural human function that most of us have, but which we interfere with when we panic or think too much. Martial arts can teach us which natural instincts are helpful and which just get in our way.

But this skill would not be very useful if the opponent could just change the direction of the push and shove you around. So, you have to develop a very low shear modulus. That way, they bounce off you only if they are on target. If they are pushing in any direction other than toward your centre, then they just drift or roll off you.

If you are really really really good at this, then you have a very high tensile modulus, a very low shear modulus, and an extremely variable bulk modulus that you almost never use.

There are some approaches to martial art that involve a very high bulk modulus, making that path to the ground as big and tough as possible. This is what we call “hard power”, and can be very effective. It can be good to have for many reasons, and I high recommend it, if you can do it.

But soft power is a martial skill that can also work when you are old and weak. This makes the centripetal geodesic as skinny as possible.

This has been compared to a steele needle wrapped in cotton. If the opponent pushes in one direction they get stabbed by the needle. But if they push in any other direction, then they meet no resistance at all.

• The needle and its high tensile modulus is one of the 13 postures.

• The low shear modulus is another.

Together, they produce the effect we call Peng and Lu. They are two sides of the same coin, and one does not function without the other. With them working together, you can plough right through an opponent’s resistance and remain unperturbed by their force.

This has also been compared to water supporting a boat. You support them by being like water. They roll over like a log or drift sideways, not because of anything you do, but merely because of the nature of water.

PRESSURE:

Now, let’s talk about pressure. Pressure is defined as the amount of force applied per unit of surface area. You can increase pressure by increasing force, or by decreasing surface area. So, if you decrease the surface that you push on or resist against, then, as the surface area approaches zero, your pressure approaches infinity. Likewise, if the opponent’s force is spread out over a larger surface, then their pressure decreases. If a needle is sharp enough, it cannot be stopped. A dull needle needs more kinetic energy to pierce a target.

To a fighter, pressure is a dangerous strategic and tactical variable, because its application confuses the proprioception of both combatants. Changing the force and surface area simultaneously makes it difficult for either of you to feel what is happening.

Sometimes we might think that increasing the surface area gives us more control. But it is really like hitting a bullet with the broadside of a barn. The pressure and control that we think we feel is force that we are receiving, not what we are dishing out. Focused pressure is effortless, which makes it difficult to feel. It is a real challenge for students to learn that easy is better, and that when you feel the force that you are applying, it is actually being applied to you.

Newton’s third law will not be contested. But you can arrange it so that the equal and opposite reaction happens when you are no longer around.

The sharpness of your needle, at that point where your opponent’s force intersects your centripetal geodesic, is another one of those 13 postures. It is called “Ji” or cramming, and there are movements, poses, and martial techniques, sometimes named after it, which are sometimes used to demonstrate and/or teach this quality.

The dullness of your opponent’s needle, or your ability to diffuse their force over a larger surface area, is another of the 13 postures. This is called “An” or press. Think of it like a wine press, which takes a grape and increases its surface area.

So, the first four postures are actually four ways to influence linear momentum. They keep you in control of your own mass and let you manipulate the opponent, in straight lines.

So, to review, The first four of the “13 postures” are:

- the centripetal geodesic, a spontaneous alignment of the opponent’s force with the path of highest tensile modulus.

- a low shear modulus at the point where the opponent’s force intersects the centripetal geodesic. In other words, no resistance against sideways pressure.

- increasing the pressure you can apply by decreasing the surface area that you connect with.

- decrease the opponent’s pressure by increasing the surface area that they connect with.

These all deal with linear velocity, and are referred to as “the four directions” traditionally called PENG, LU, JI, and AN.

When it comes to angular velocity, tai chi has “the four corners”, traditionally called CAI, LIEH, ZHOU, KAO.

Angular Momentum and Torque

CAI, LIEH, ZHOU, and KAO, are usually translated as “pluck, rend, elbow, and shoulder” because there are martial techniques with these names, and these techniques are used as examples of the four corners. But that tends to confuse the point.

Cai and Lieh are concerned with torque.

If you try to close a door, you can do it with less movement if you push near the hinge than if you push near the doorknob, but it requires much more force.

If you apply the force farther from the hinge, it requires less force, but you have to push farther.

Likewise, if you try to push me around, you can either use more force close to the centre of rotation or less force farther from the centre of rotation.

Now, let’s say you apply force to my arm close my centre. If I move your force away from my centre, you might think you could generate torque more easily. But in so doing, I also decrease the angle of your force, direct your force away from my centre, and increase the arc length beyond what you are prepared to deal with. The reduction in the angle reduces the torque and the increasing arc length means you have to travel farther for the same result.

Increasing the distance of your force from my centre is what we call splitting. The traditional term is LIEH. 挒. Sometimes it is done by extending the arms, like lengthening the spokes on a wheel. Sometimes it is simply a matter of changing the shape of the arms, so that the opponent’s force is redirected like the wake of a boat as the boat splits the water.

Now let’s say your opponent is turning their own body and using torque to apply force with their hand or fist. If you can increase the distance between their hand and their centre, then they will need to use more torque to generate the same amount of force. Try pushing something sideways with your hand close to your body. Next, try pushing the same thing with your hand extended straight out to your side.

Causing the opponent’s force to move away from their own centre of rotation is called cǎi 採, which means to gather, or pluck. Like taking a fruit from a tree, you are taking the opponent’s force away from their centre. It can also draw their centre away from the earth.

Cai and Lieh are ways of dealing with someone who tries to grab, twist, or otherwise manipulate your centripetal geodesic, like trying to grab a needle.

But what if the opponent wants to make your needle collapse? What if they disconnect your centripetal geodesic in a way that prevents you from connecting their force to the ground? In martial arts, this is often called trapping. They might trap your arms against your body in a way that prevents you from properly engaging the ground. This is what happens when we do zhǒu 肘. There can be some confusion about this. Zhou translates as “elbow”, and there is a technique called zhou which involves striking with the elbow. But when you strike with the elbow, what you are doing is getting past the opponent’s power. You bypass the tip of their needle and attack their centripetal geodesic from the inside…or the side. If the don’t adapt, they will not have a leg to stand on, and they won’t be able to effectively engage your force.

Now, what if someone does that to you. Well, the first answer is, don’t let them. But there are two commonly useful answers. One is that you can sometimes use LIEH, to move them away from your centre. Another is that you can use KAO.

Kao is often translated as Shoulder stroke. A better translation is “against” or “abutting”. I call it shortening the needle.

If the opponent gets past the end of your centripetal geodesic, then let the needle break. Remember that low shear modulus? Let go of that long arm and sharpen what is left of the needle. Even if they make it to your shoulder, head, hips, or legs, you can still connect them to the ground, or your centre, as long as you are willing to relax and change shape.

The actual shape is not as important as the connection.

Self defence often depends on your ability to avoid dangerous attachments to particular definitions of self. Too many people fall down stairs because they were not willing to let go of the boxes they were carrying.

So, now we have the first 8 of the thirteen postures.

The first four are called ”the four directions” and deal with linear momentum and pressure:

High tensile connection to the centre, with a low shear modulus, that focuses your own force while diffusing the opponent’s force.

The second four are called “the four corners” and deal with angular momentum:

Increasing the distance of the opponent’s force from your centre of rotation, and from their centre of rotation, while collapsing their connection to the centre, and preserving your connection under any circumstance.

These eight are called the ”eight trigrams in the hands.” They limit the role of the arms to regulating alignment, aim and reach. The arms should not be used to apply force, because they cannot do so without decreasing the mechanical advantage. All the joints in the arm are class three levers, which have a negative mechanical advantage, and using them to generate force will break the centripetal geodesic, and complicate the vectors beyond mind’s ability to coordinate. It would be like juggling 16 balls instead of three.

THE LEGS

To understand this reasoning, imagine that you are shovelling snow. If the snow is light and fluffy, you can shovel it with your arm and back muscles. But if it the wet snow or frozen formerly wet snow left at the end of your driveway as plow wake, then those class 3 levers in your arms are not going to work very well. Now you have to lock your arms into the strongest structural alignment, and use your legs to turn your whole body into a class one lever, pry that snow into the air, carry it to the side of the driveway, and roll it off the shovel.

Here is another example. This wood is too heavy for me to lift using my arm muscles. Each class three lever makes the attempt more futile. But if I use my legs and my hips, then I can increase the mechanical advantage and toss it into the air. If you try this yourself, start with something easy, and don’t let it touch your side unless you absolutely have to.

The legs move the body in 6 degrees of freedom. (Surge, heave, sway, pitch, yaw and roll.) The arms can add to that. But we don’t want them to do so in a way that interferes with the force and leverage of the legs. Therefore it is said that the power is generated in the legs, directed by the waist, and expressed by the hands. Do not try to generate power with the hands.

In the 13-postures theory, there are 5 things that can be done with the legs. These are traditionally called “advance, retreat, look right, gaze left, and central equilibrium.”

Well.

That is not very helpful.

Let’s call them “regulate force, regulate space, class two lever, class one lever, and the axis of rotation.”

”Advance” is better translated as ”apply variable force:”

The legs, by controlling the 6 degrees of freedom, can increase or decrease the force you use. This can be in any direction. It can be in more than one direction at a time, depending on your position relative to the opponent or opponents.

You don’t have to be moving forward to increase forward pressure. For example, a boxer can knock an opponent out with a left punch while moving backwards.

”Retreat” is better translated as “create space.”

The legs can create space between you and your opponent. You can do this by moving the body in any direction that creates more room.

“Central Equilibrium” refers to the fact that the legs determine the axis of rotation. The most common choices are the left or right vertical axis corresponding to the hips or axillary lines, the central vertical axis, and the horizontal axis of the hips or waist. For most students, 99% of the time will be spent on these choices. But, over time, you will discover some very interesting variations that include diagonal axes, barycentric axes, and the interactions with external axes.

“Look right” is better translated as “class 2 lever.”

If your right leg in forward and you pivot clockwise around the right hip, it is a bit like looking around a corner. This is also the movement of techniques like “ward off” or “peng” or a right backfist, or some other punches, which function as class 2 levers, with the load between the fulcrum and the effort.

“Gaze left” is better translated as “class 1 lever.”

If your right leg is forward and you pivot counter-clockwise around the right hip, it is a bit like turning away from the wall to gaze off into the distance. This is found in movements like a right cross or a right hook, or “repulse the monkey,” or “high pat on horse,” which have the fulcrum between the load and the effort.

At some point, you will likely ask, “Why can’t you look right and gaze left.”

The answer, of course, is that you can. But traditional tai chi is very right handed. The traditional Yang style routine does “grasp the bird’s tail” 13 times on the right side, and never on the left. When asked why he didn’t teach it on the other side, one revered teacher said, “Do you right with both hands?”

Myself, I teach symmetrical routines. I think the focus on right handed techniques might have been routed in cultural habits that go back to the days before toilet paper and hand soap. Many cultures, all over the world, have long had aversions to anything left-handed. Or, perhaps there is a school of thought that tries to keep the dominant hand forward. I don’t know.

But for me, teaching both sides equally is a given in my school.

So, those are the “5 elements in the feet.” Force, space, axis of rotation, class 1 lever, and class 2 lever.

All of these can be applied simultaneously. A class 2 lever with one leg, a class 1 lever with the other, increasing force while increasing space.

You can also do all of these while diffusing the opponent’s pressure, focusing your own tensile geodesic, increasing the subjective force radius and the objective force radius, breaking the opponent’s connection and preserving your own.

The thirteen postures are actually 13 mechanical efficiencies that can be applied in thousands of different ways.

But the goal should not just be to apply them to individual techniques, but to make them spontaneous and natural, so that the mechanical advantage is your default position. This way, you will always have the strongest position. Each fight will start with you winning, even if you never start the fight.