Basic Terminology: Chi / Qi

There is chi in tai chi but the chi in tai chi it is different from the chi in tai chi.

Yes. You heard me.

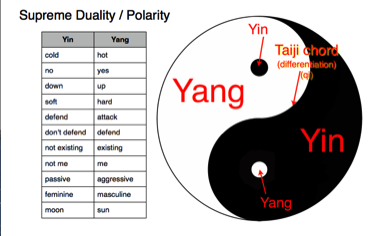

Previously, I told you about the different spellings and meanings of Tai chi and Tai chi chuan. I explained that tai chi is the philosophical concept of yin and yang, and that “tai chi chuan” is the art form/exercise/sport/therapy/meditation/martial art that bases its training methods, tactics, and strategy on the concept of yin and yang. I also explained that “Tai chi chuan” is usually abbreviated as simply “tai chi.” So, “tai chi” is both the philosophy and the art based on that philosophy.

That is one word, two meanings, several spellings, and one pronunciation (more or less).

Now we have to talk about chi 气 , not to be confused with chi 极. To non-Chinese-speakering people, it is one word with two spellings and one pronunciation, and several different meanings. To Chinese-speaking people, they are two different words with different spellings and even more different meanings.

Oh boy. Stay with me. We will get through this.

When speaking Chineses, the word “Chi”1 in the word “Tai chi” , sounds different from the Chi 2 in Chi kung (Qigong). Non Chinese-speaking anglophones are oblivious to the difference, and so, confuse the two words.

The art of tai chi includes the practice of what is, nowadays, called Chi Kung (qigong). But the chi(ji) in tai chi is a different word from the word chi(qi) in Chi Kung (qigong).

The word chi [jí] in “tai chi” means extremity or pole (as in North Pole) or dipole. The word chi [qi] that is often used by tai chi teachers when teaching tai chi, does not.

In English, whether spelled “chi” or “qi”, the word is pronounced “chee.”

The established English spelling for Tai chi comes from the Wade Giles romanization which was “t’ai chi ch’üan” and has been simplified in general use. Scholars have tried to get people to use the pinyin romanization “taijiquan” to avoid confusion. But that just confuses the general public. Internet searches for “tai chi” greatly outnumber searches for “taijiquan.”

To avoid the confusion between “tai chi” and “chi” many will use the Chinese Pinyin romanization, “Qi,” to avoid confusion. But that leads to people pronouncing it like “key” instead of “chee” which is closer to the proper Chinese pronunciation. If you correct people and tell them that “key” is incorrect, some will then point out that the Japanese pronunciation of chi [qi] is actually “ki.” Since many in the west have studied Japanese arts like aikido, (oh boy… here we go) which talks a lot about chi, but pronounces it the Japanese way, which is “Ki.” By the way, the “ki” in Aikido is the same character as ki/chi/qi/ 气 /氣.

When the English language borrows words from other languages, it sometimes keeps the original spelling and pronunciation, and sometimes changes one or the other. “Faux pas” is not pronounced “Fox Pass” in spite of the way it is spelled. We could spell it “Pho Pa” and confuse it with Vietnamese. The word Lieutenant might be pronounced “lee-uh-tenant,” or left-enant.” It could be pronounced “loo-tenant” as it is in the USA, even though that sounds like someone who lives in a toilet.

But anyway, back to chi.

What does chi [qì] mean, then?

I’m so glad you asked. *sigh*

Here are a couple of dictionary definitions:

气(F氣) [qì] air, vapor; vital energy; 天气 tiānqì weather 3

气[氣]¹qì {B} n. ①air; gas ②smell ③spirit; vigor; morale ④vital/material energy (in Ch. metaphysics) ⑤tone; atmosphere; attitude ⑥anger ⑦breath; respiration ◆b.f. ①weather 天气 tiānqì ②〈lg.〉 aspiration 送气 sòngqì ◆v. ①anger | Qì de wǒ shuōbuchū huà. 气得我说不出话。 I was too angry to speak. ②get angry ③bully; insult 4

In the practice of tai chi, the word qi sometimes refers to breath. Sometimes it refers to vitality. Sometimes it refers to bioelectric energy, or electromagnetism. Sometimes it refers to kinetic energy. Sometimes it refers to aspects of structural integrity. Sometimes it refers to the potential response of the elastic modulus of tensegrity structures in the body. Sometimes it refers to a relationship between mind and body. Sometimes it refers to…

I could go on, and I will, in a later lesson.

Internal Skill

There is an aspect of traditional tai chi training called “internal training.” It is the subtle development of breath, posture, proprioception, and the harmonizing of mind, body, and spirit. It includes meditation, visualization, stretching, breathing, postures, and movement. There are different approaches, depending on the tai chi school, teacher, lineage, and style.

Nèi gōng 内功 translates as “internal cultivation.”

Nèi dān 内丹 translates as “internal alchemy.”

Qigong / Chi Kung ( Qìgōng 气功 / 氣功 ) (say “Chee Gong”) is term coined by Liu Guizhen 5 in 1949 to refer to a standardized approach to internal health practices.

Nowadays, few people can make a distinction between neigong, neidan, and qigong. The terms are often used interchangeably, or grouped under the category of qigong. So, now we talk about the thousands of different schools of qigong, including medical qigong, Daoist qigong, buddhist qigong, emitting absorbing and healing qigong, and martial arts qigong.

Decades ago, if you asked a tai chi master about learning qigong, old masters would say that you don’t need to practice qigong. Just to tai chi. All the benefits of qigong are included in tai chi practice.

But in recent times, qigong has become an umbrella term for internal practices. At the same time, tai chi has become compartmentalized or simplified. Many schools have lost the original internal practices of tai chi and need to supplement the art with other qigong practices.

The role of qi in tai chi chuan

In so far as qi means breath, it is vitally important. You must breathe. There is a different appropriate breathing method for every situation in life. However, I make it a point to avoid stressing my students about breathing. I say, “Breathe in, then breathe out. Then repeat if necessary.” One should not try to coordinate the breath with the movement, especially in the beginning. That would just make you tense. Later, you can let the movement follow the breath. But that is not a hard and fast rule.

In so far as qi means energy, that is unavoidable but also subjective. I don’t tell my students to expect any particular energy sensations, and I don’t talk about my own experiences with qi. In fact, I try to avoid talking about qi until the students start to notice subtle changes.

I focus on refining the mundane skills until the students find the subtle. Then they we evade delusion until the student finds the profound. Then we evade delusion until the student discovers the mysterious. Throughout the journey, discernment is the most important skill.

Qi is real. But our perception of it is entirely subjective There is no actual mechanism for sensing qi. The best we can do is interpret its effect.

It is the same thing when we study physics. We can talk about energy and matter. But there is no way to experience them directly. We cannot see light, because light is what we see with. If we could see light, we would not be able to see anything else. The light would be in the way.

Qi is the separation between yin and yang. It defines our experience of the universe. But we cannot directly experience qi itself.